When Punjab National Bank told the RBI in December 2025 about a ₹2,434 crore loan fraud linked to the SREI Group, the number sounded frightening. Large fraud figures usually mean losses, falling profits, and nervous investors.

But this case was different. PNB had already set aside the full amount as provisions. The loss had been recognised earlier. There was no fresh hit to the bank’s profits and no damage to its balance sheet.

This episode is important not because PNB suffered a loss, but because it shows how complex corporate frauds can go unnoticed for years—even by large and experienced banks—and why such events are closely tracked by market participants seeking reliable swing stock trading advice in India.

Who Was SREI? From Glory to Infamy

SREI Group was once a respected name in India’s infrastructure financing space. It was founded in 1989 by the Kanoria family in Kolkata. Over the years, SREI became a key lender to construction and mining companies. At its peak, the group claimed that nearly one out of every three heavy machines in India was financed by it.

The business mainly ran through two NBFCs—SREI Equipment Finance Limited (SEFL) and SREI Infrastructure Finance Limited (SIFL). These companies borrowed money from banks and then lent it to infrastructure and equipment buyers.

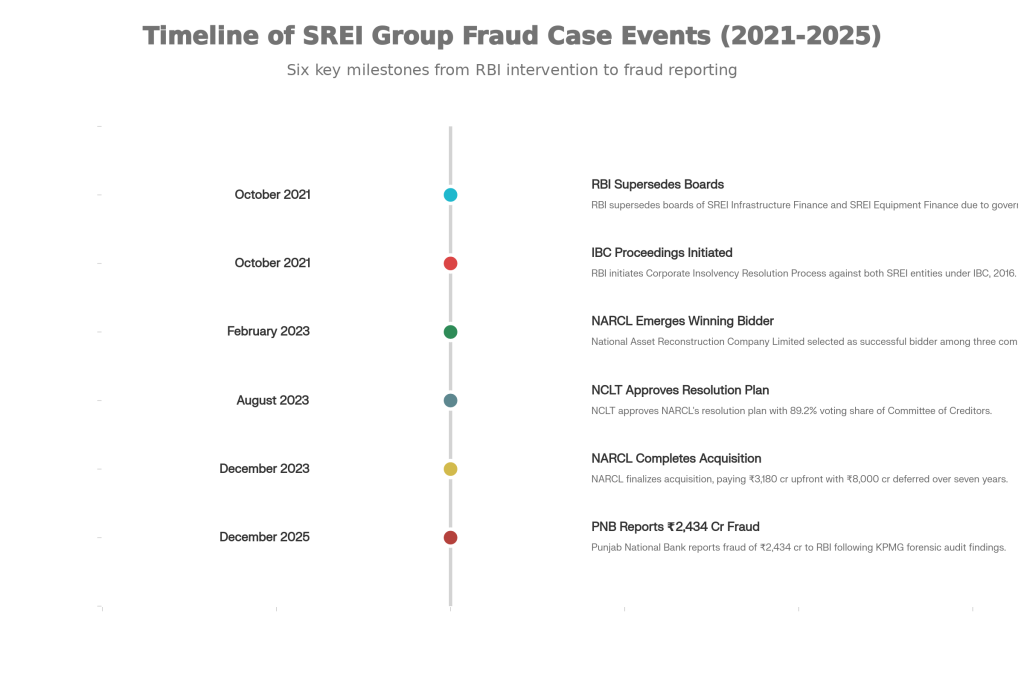

Problems started becoming visible around 2020. Loan repayments slowed, cash flow tightened, and doubts about management practices increased. In October 2021, the RBI stepped in, removed the boards of both companies, and sent them into insolvency.

By then, SREI’s total debt had grown to about ₹32,700 crore, making it one of the biggest NBFC failures in India.

How the Fraud Worked: A Masterclass in Deception

SREI’s collapse was not just the result of bad business decisions. A forensic audit later showed that there was deliberate cheating involved.

Old loans that were not being repaid were kept alive by giving new loans. This practice, called evergreening, helped hide the true level of stress in the loan book.

Large amounts of money were lent to companies that were linked to insiders. These were shown as normal business loans, but in reality the money was moving within the group. Around ₹8,158 crore was routed to such connected entities.

Asset values were also inflated. Equipment worth only a few lakhs was shown as worth several crores. This helped SREI borrow more money from banks than it should have.

Funds taken for equipment financing were used for other purposes. Some loans were given at very low interest rates during moratorium periods, sometimes as low as 1%, even though internal calculations showed much higher returns. These were clear warning signs that were missed.

Why the Four-Year Delay?

Many people ask why the fraud was reported in 2025 when insolvency started in 2021. The reason lies in how fraud is defined under banking rules.

Not every failed loan is fraud. Fraud means there was clear intention to mislead. To prove this, banks must depend on detailed forensic audits and strong evidence.

If a bank declares fraud too early, it can affect insolvency proceedings. If it declares it without proof, legal action may fail. PNB waited until the forensic audit clearly confirmed wrongdoing before reporting the case to the RBI.

The Resolution: NARCL Saves the Day

While the fraud investigation was going on, the insolvency process continued. In February 2023, the government-backed National Asset Reconstruction Company Limited (NARCL) took over SREI’s bad loans.

In August 2023, the NCLT approved the resolution plan with strong support from lenders. Under this plan, banks agreed to recover about 45% of their dues, meaning a haircut of around 55%.

Banks received ₹3,180 crore upfront. The remaining amount of around ₹8,000 crore will be paid over the next several years. For a case involving more than ₹32,000 crore of debt, this was seen as a reasonable outcome.

Why PNB Investors Shouldn’t Panic

For PNB shareholders, the key point is simple. The bank had already taken the full loss earlier through provisions.

Provisioning means setting aside money in advance to cover possible losses. Because PNB had done this, the fraud declaration did not hurt future profits.

That is why PNB’s share price hardly reacted when the news came out. The market already knew the damage had been accounted for.

The Domino Effect: Other Banks Follow

PNB was not the only lender involved. Other banks, including Bank of Baroda, Union Bank of India, Punjab & Sind Bank, and Suryoday Small Finance Bank, also declared their SREI loans as fraud.

This shows a change in how banks are behaving. Instead of quietly writing off bad loans, they are now openly reporting fraud and pushing for accountability.

What Happens Next: Criminal Action

Once a loan is declared as fraud, criminal action can begin. Banks can file complaints with the CBI for cheating and misuse of funds.

The Enforcement Directorate may also step in to check for money laundering. If the promoters are found guilty, their personal assets such as property and investments can be seized. Banks can also continue civil cases to recover money.

Why This Fraud Reveals Systemic Lessons

The SREI case highlights several weak points in the system. Asset checks were poor, physical verification was weak, and too much trust was placed on the promoters’ reputation.

Related-party transactions were cleverly structured to avoid detection. Older systems and manual processes failed to spot these patterns in time.

These problems were also seen earlier during the IL&FS crisis and the NBFC slowdown of 2018–19.

The Regulatory Evolution: Fraud Detection Gets Smarter

Since then, the RBI has made several changes. Fraud reporting timelines are tighter. Forensic audits are compulsory for large cases. NBFCs face closer monitoring, and related-party transactions receive more attention.

Banks also use better technology to track loans and fund movement. Because of these improvements, a case like SREI would likely be caught much earlier today.

The Bigger Picture: System Resilience

Despite the size of the failure, the overall response was strong. RBI stepped in early, insolvency moved forward, lenders recovered part of their money, and fraud was finally identified.

For investors and depositors, this reinforces the idea that despite periodic failures, the system can absorb losses and evolve—an insight frequently shared by any SEBI registered stock advisory in banking-sector analysis.

The Verdict

SREI’s fall from a trusted infrastructure lender to a fraud case is a serious warning. But it also shows that India’s banking system is learning from past mistakes.

If this case leads to better checks, faster detection, and stricter action against wrongdoing, then the ₹2,434 crore loss will help make the system safer in the long run.